Vincent Sarich and Frank Miele, Race: The Reality of Human Differences (Cambridge, MA: Westport Press 2004)

First published in 2004, ‘Race: The Reality of Human Differences’ by anthropologist and biochemist Vincent Sarich and science writer Frank Miele is that rarest of things in this age of political correctness – namely, a work of popular science presenting a hereditarian perspective on that most incendiary of topics, namely the biology of race and of racial differences.

It is refreshing that, even in this age of political correctness, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, a mainstream publisher still had the courage to publish such a work.

On first embarking on reading ‘Race: The Reality of Human Differences’ I therefore had high expectations, hoping for something approaching an updated, and more accessible, equivalent to John R Baker’s seminal ‘Race’ (which I have reviewed here).

Unfortunately, however, ‘Race: The Reality of Human Differences’, while it contains much interesting material, is nevertheless, in my view, a disappointment and something of a missed opportunity.

Race and the Law

Despite their subtitle, Sarich and Miele’s primary objective in authoring ‘Race: The Reality of Human Differences’ is, it seems, not to document, or to explain the evolution of, the specific racial differences that exist between populations, but rather to defend the race concept itself.

The latter has been under attack at least since Ashley Montagu’s Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, first published in 1942, perhaps the first written exposition of race denial.

Thus, Sarich and Miele frame their book as a response to the then-recent PBS documentary ‘Race: The Power of an Illusion’, which, like Montagu, also espoused the by-then familiar line that human races do not exist, save as a mere illusion or ‘social construct’.

As evidence that, on the contrary, race is indeed a legitimate biological and taxonomic category, Sarich and Miele begin by discussing, not the field of biology, but rather that of law, discussing the recognition accorded the race concept under the American legal system.

They report that, in the USA:

“There is still no legal definition of race; nor… does it appear that the legal system feels the need for one” (p14).

Thus, citing various US legal cases where race of the plaintiff was at issue, Sarich and Miele conclude:

“The most adversarial part of our complex society [i.e. the legal system], not only continues to accept the existence of race, but also relies on the ability of the average individual to sort people into races” (p14).

Moreover, Sarich and Miele argue, not only do the courts recognise the existence of race, they also recognise its ultimate basis in biology.

Thus, in response to the claim that race is a mere ‘social construct’, Sarich and Miele cite the recognition the criminal courts accord to the evidence of forensic scientists, who can reliably determine the racial background of a criminal from microscopic DNA fragments (p19-23).

“If race were a mere social construction based upon a few highly visible features, it would have no statistical correlation with the DNA markers that indicate relatedness” (p23).[1]

Indeed, in criminal investigations, Sarich and Miele observe in a later chapter, racial identification can be a literal matter of life and death.

Thus, they refer to the Baton Rouge serial killer investigation, where, in accordance with the popular, but wholly false, notion that serial killers are almost invariably white males, the police initially focussed solely on white suspects, but, after DNA analysis showed that the offender was of predominantly African descent, shifted the focus of their investigation and eventually successfully apprehended the killer, preventing further killings (p238).[2]

Another area where they observe that racial profiling can be literally a matter of life and death is the diagnosis of disease and prescribing of appropriate and effective treatment – since, not only do races differ in the prevalence, and presentation, of different medical conditions, but they also differ in their responsiveness and reactions to different forms of medication.

However, while folk-taxonomic racial categories do indeed have a basis in real biological differences, they are surely also partly socially-constructed as well.

For example, in the USA, black racial identity, including eligibility for affirmative action programmes, is still largely determined by the same so-called ‘one-drop-rule’ that also determined racial categorization during the era of segregation and Jim Crow.

This is the rule whereby a person with any detectable degree of black African ancestry, howsoever small (e.g. Barack Obama, Colin Powell), is classed as ‘African-American’ right alongside a recent immigrant from Africa of unadulterated sub-Saharan African ancestry.

This obviously has far more to do with social and political factors, and with America’s unique racial history, than it does with biology and hence shows that folk-taxonomic racial categories are indeed part ‘socially-constructed’.[3]

Similarly, the racial category ‘Hispanic’ or ‘Latino’ obviously has only a distant and indirect relationship to race in the biological sense, including as it does persons of varying degrees of European, Native American and also black African ancestry.[4]

It is also unfortunate that, in their discussion of the recognition accorded the race concept by the legal system, Sarich and Miele restrict their discussion entirely to the contemporary US legal system.

In particular, it would be interesting to know how the race of citizens was determined under overtly racialist regimes, such as under the Apartheid regime in South Africa,[5] under the Nuremberg laws in National Socialist Germany,[6] or indeed under Jim Crow laws in the South in the USA itself in the early twentieth century,[7] where the stakes were, of course, so much higher.

Also, given that Sarich and Miele rely extensively in later chapters on an analogy between human races and dog breeds (what he calls the “canine comparison”: p198-203; see discussion below), a discussion of the problems encountered in drafting and interpreting so-called breed-specific legislation to control so-called ‘dangerous dog breeds’ would also have been relevant and of interest.[8]

Such legislation, in force in many jurisdictions, restricts the breeding, sale and import of certain breeds (e.g. Pit Bulls, Tosas) and orders their registration, neutering and sometimes even their destruction. It represents, then, the rough canine equivalent of the Nuremberg laws.

A Race Recognition Module?

According to Sarich and Miele, the cross-cultural universality of racial classifications suggests that humans are innately predisposed to sort humans into races.

As evidence, they cite Lawrence Hirschfeld’s finding that, at age three, children already classify people by race, and recognise both the immutable and hereditary nature of racial characteristics, giving priority to race over characteristics such as clothing, uniform or body-type (p25-7; Hirschfeld 1996).[9]

Sarich and Miele go on to also claim:

“The emerging discipline of evolutionary psychology provides further evidence that there is a species-wide module in the human brain that predisposes us to sort the members of our species into groups based on appearance, and to distinguish between ‘us’ and ‘them’” (p31).

However, they cite no source for this claim, either in the main body of the text or in the associated notes for this chapter (p263-4).[10]

Certainly, Pierre van den Berghe and some other sociobiologists have argued that ethnocentrism is innate (see The Ethnic Phenomenon: reviewed here). However, van den Berghe is also emphatic and persuasive in arguing that the same is not true of racism, as such.

Indeed, since the different human races were, until recent technological advances in transportation (e.g. ships, aeroplanes), largely separated from one another by the very oceans, deserts and mountain-ranges that reproductively isolated them from one another and hence permitted their evolution into distinguishable races, it is doubtful human races have been in contact for sufficient time to have evolved a race-classification module.[11]

Moreover, if race differences are indeed real and obvious as Sarich and Miele contend, then there is no need to invoke – or indeed to evolve – a domain-specific module for the purposes of racial classification. Instead, people’s tendency to categorise others into racial groups could simply reflect domain-general mechanisms (i.e. general intelligence) responding to real and obvious differences.[12]

History of the Race Concept

After their opening chapter on ‘Race and the Law’, the authors move on to discussing the history of the race concept and of racial thought in their second chapter, which is titled ‘Race and History’.

Today, it is often claimed by race deniers that the race concept is a recent European invention, devised to provide a justification for such nefarious, but by no means uniquely European, practices as slavery, segregation and colonialism.[13]

In contrast, Sarich and Miele argue that humans have sorted themselves into racial categories ever since physically distinguishable people encountered one another, and that ancient peoples used roughly the same racial categories as nineteenth-century anthropologists and twenty-first century bigots.

Thus, Sarich and Miele assert in the title of one of their subheadings:

“[The concept of] race is as old as history or even prehistory” (p57).

Indeed, according to Sarich and Miele, even ancient African rock paintings distinguish between Pygmies and Capoid Bushmen (p56).

Similarly, they report, the ancient Egyptians showed a keen awareness of racial differences in their artwork.

This is perhaps unsurprising since the ancient Egyptians’ core territory was located in a region where Caucasoid North Africans came into contact with black Africans from South of the Sahara through the Nile Valley, unlike in most other parts of North Africa, where the Sahara Desert represented a largely insurmountable barrier to population movement.

While not directly addressing the controversial question of the racial affinities of the ancient Egyptians, Sarich and Miele report that, in their own artwork:

“The Egyptians were painted red; the Asiatics or Semites yellow; the Southerns or Negroes, black; and the Libyans, Westerners or Northerners, white, with blue eyes and fair beards” (p33).[14]

Indeed, rather than being purely artistic in intent, Sarich and Miele go further, even suggesting that at least some Egyptian artwork had an explicit taxonomic function:

“[Ancient] Egyptian monuments are not mere ‘portraits but an attempt at classification’” (p33).

They even refer to what they call “history’s first [recorded] colour bar, forbidding blacks from entering Pharaoh’s domain”, namely an an Egyptian stele (i.e. stone slab functioning as a notice), which other sources describe as having been erected during the reign of Pharaoh Sesostris III (1887-1849 BCE) at Semna near the Second Cataract of the Nile, part of the inscription of which reads, in part:

“No Negro shall cross this boundary by water or by land, by ship or with his flocks, save for the purpose of trade or to make purchases in some post” (p35).[15]

Sarich and Miele also interpret the famous caste system of India as based ultimately in racial difference, the lighter complexioned invading Indo-Aryans establishing the system to maintain their dominant social position and their racial integrity vis à vis the darker-complexioned indigenous Dravidian populations whom they conquered and subjugated.

Thus, Sarich and Miele claim:

“The Hindi word for caste is varna. It means color (that is, skin color), and it is as old as Indian history itself” (p37).[16]

There is indeed evidence of racial prejudice and notions of racial supremacy in the earliest Hindu texts. For example, in the Rigveda, thought to be the earliest of ancient Hindu texts:

“The god of the Aryas, Indra, is described as ‘blowing away with supernatural might from earth and from the heavens the black skin which Indra hates.’ The dark people are called ‘Anasahs’—noseless people—and the account proceeds to tell how Indra ‘slew the flat-nosed barbarians.’ Having conquered the land for the Aryas, Indra decreed that the foe was to be ‘flayed of his black skin’” (Race: The History of an Idea in America: p3-4).[17]

Indeed, higher caste groups have relatively lighter complexions than lower caste groups residing in the same region of India even today (Jazwal 1979; Mishra 2017).

However, most modern Indologists reject the notion that the term ‘varna’ was originally coined in reference to differences in skin colour and instead argue that colour was simply used as a method of classification, or perhaps in reference to clothing.[18]

According to Sarich and Miele, ancient peoples also believed races differed, not only in morphology, but also in psychology and behaviour.

In general, ancient civilizations regarded their own race’s characteristics more favourably than those of other groups. This, Sarich and Miele suggest, reflected, not only ethnocentrism, which is, in all probability, a universal human trait, but also the fact that great civilizations of the sort that leave behind artwork and literature sophisticated enough to permit moderns to ascertain their views on race did indeed tend to be surrounded by less advanced neighbours (p56).

“In the vast majority of cases, their opinions of other peoples, including the ancestors of the Western Europeans who supposedly ‘invented’ the idea of race, are far from flattering, at times matching modern society’s most derogatory stereotypes” (p31).

Thus, Thomas F Gossett, in his book Race: The History of an Idea in America, reports that:

“Historians of the Han Dynasty in the third century B.C. speak of a yellow-haired and green-eyed barbarian people in a distant province ‘who greatly resemble monkeys from whom they are descended’” (Race: The History of an Idea in America: p4).

Indeed, the views expressed by the ancients regarding racial differences, or at least those examples quoted by Sarich and Miele, are also often disturbingly redolent of modern racial stereotypes.

Thus, in ancient Roman and Greek art, Sarich and Miele report:

“Black males are depicted with penises larger than those of white figures” (p41).

Likewise, during the Islamic Golden Age, Sarich and Miele report that:

“Islamic writers… disparaged black Africans as being hypersexual yet also filled with simple piety, and with a natural sense of rhythm” (p53).

Similarly, the Arab polymath Al Masudi is reported to have quoted the Roman physician-philosopher Galen, as claiming blacks possess, among other attributes:

“A long penis and great merriment… [which] dominates the black man because of his defective brain whence also the weakness of his intelligence” (p50).

From these and similar observations, Sarich and Miele conclude:

“European colonizers did not construct race as a justification for slavery but picked up an earlier construction of Islam, which took it from the classical world, which in turn took it from ancient Egypt” (p50).

The only alternative, they suggest, is the obviously implausible suggestion that:

“Each of these civilisations independently ‘constructed’ the same worldview, and that the civilisations of China and India independently ‘constructed’ similar worldviews, even though they were looking at different groups of people” (p50).

There is, of course, another possibility the authors never directly raise, but only hint at – namely, perhaps racial stereotypes remained relatively constant because they reflect actual behavioural differences between races that themselves remained constant simply because they reflect innate biological dispositions that have not changed significantly over historical time.

Race, Religion, Science and Slavery

Sarich and Miele’s next chapter, ‘Anthropology as the Science of Race’, continues their history of racial thought from biblical times into the age of science – and of pseudo-science.

They begin, however, not with science, or even with pseudo-science, but rather with the Christian Bible, which long dominated western thinking on the subject of race, as on so many other subjects.

At the beginning of the chapter, they quote from John Hartung’s controversial essay, Love Thy Neighbour: The Evolution of In-Group Morality, which was first published in the science magazine, Skeptic (p60; Hartung 1995).

However, although the relevant passages appear in quotation marks, neither Hartung himself, nor his essay is directly cited, and, where I not already familiar with this essay, I would be none the wiser as to where this series of quotations had actually been taken from.[19]

In the passage quoted, Hartung, who, in addition to being an anaesthesiologist, anthropologist and human sociobiologist, known for his pioneering cross-cultural studies of human inheritance patterns, is also something of an amateur (atheist) biblical scholar, argues that Adam, in the Biblical account of creation, is properly to be interpreted, not as the first human, but rather only as the first Jew, the implication being that, and the confusion arising because, in the genocidal weltanschauung of the Old Testament, non-Jews are, at least according to Hartung, not really to be considered human at all.[20]

This idea seems to have originated, or at least received its first full exposition, with theologian Isaac La Peyrère, whom Sarich and Miele describe only as a “Calvinist”, but who, perhaps not uncoincidentally, is also widely rumoured to be of Sephardi converso or even crypto-Jewish marrano ancestry.

Thus, Sarich and Miele conclude:

“The door has always been open—and often entered—by any individual or group wanting to confine ‘adam’ to ‘us’ and to exclude ‘them’” (p60).

This leads to the heretical notion of the pre-Adamites, which has also been taken up by such delightfully bonkers racialist religious groups as the Christian Identity movement.[21]

However, mainstream western Christianity always rejected this notion.

Thus, whereas today many leftists associate atheism, the Enlightenment and secularism with anti-racist views, historically there was no such association.

On the contrary, Sarich and Miele emphasize, it was actually polygenism – namely, the belief that the different human races had separate origins, a view that naturally lent itself to racialism – that was associated with religious heresy, free-thinking and the Enlightenment.

In contrast, mainstream Christianity, of virtually all denominations, has always favoured monogenism – namely, the belief that, for all their perceived differences, the various human races nevertheless shared a common origin – as this was perceived as congruent with (the orthodox interpretation of) the Old Testament of the Bible.

Thus, Isaac La Peyrère was actually imprisoned for his heretical polygenism and released only after agreeing to recant his heretical views, while others who explored similar ideas – such as Giordano Bruno, who denied that Jews and Ethiopians in particular could possibly share the same ancestry, and Lucilio Vanini, who, anticipating Darwin’s theory of evolution, ventured the view that ‘Ethiopians’, i.e black people, and only black people, might be descended from monkeys – were actually burnt at the stake for these and other heretical ideass (Race: The History of an Idea in America: p15).

Meanwhile, such eminent luminaries of enlightenment secularism as Voltaire and David Hume also identified as polygenists – and, although their experience with and knowledge of black people was surely minimal and almost entirely second-hand, both also expressed distinctly racist views regarding the intellectual capacities of black Africans.

Moreover, although the emerging race science, and cranial measurements, of the nineteenth century ‘American School’ of anthropology is sometimes credited with lending ideological support to the institution of slavery in the American South, or even as being cynically formulated precisely in order to defend this institution, in fact Southern slaveholders had little if any use for such ideas.

After all, the American South, as well as being a stronghold of slavery, racialism and white supremacist ideology, was also, then as now, the ‘Bible Belt’ – i.e. a bastion of intense evangelical Protestant Christian fundamentalism.

But the leading American School anthropologists, such as Samuel Morton and Josiah Nott, were all heretical polygenists.

Thus, rather than challenge the orthodox interpretation of the Bible, Southern slaveholders, and their apologists, preferred to defend slavery by invoking, not the emerging secular science of anthropology, but rather Biblical doctrine.

In particular, they sought to justify slavery by reference to the so-called ‘curse of Ham’, an idea which derives from Genesis 9:22-25, a very odd passage of the Old Testament (odd even by the standards of the Old Testament), which was almost certainly not originally intended as a reference to black people.[22]

Thus, the authors quote historian William Stanton, who, in his book The Leopard’s Spots: Scientific Attitudes Toward Race in America 1815-59 concludes that, by rejecting polygenism and the craniology of the early American physical anthropologists:

“The South turned its back on [what was by the scientific standards of the time] the only intellectually respectable defense of slavery it could have taken up” (p77)

As for Darwinism, which some creationists also claim was used to buttress slavery, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was only published in 1959, just a couple of years before the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 and final abolition of slavery in North America and the English-speaking world.[23]

Thus, if Darwinian theory was ever used to justify the institution of slavery, it clearly wasn’t very effective in achieving this end.

Into the ‘Age of Science’ – and of Pseudo-Science

The authors continue their history of racial thinking by tracing the history of the discipline of anthropology, from its beginnings as ‘the science of race’, to its current incarnation as the study of ‘culture’ (and, to a lesser extent, of human evolution), most of whose practitioners vehemently deny the very biological reality of race, and some of whom deny even the possibility of anthropology being a science.

Giving a personal, human-interest focus to their history, Sarich and Miele in particular focus on three scientific controversies, and personal rivalries, each of which were, they report, at the same time scientific, personal and political (p59-60). These were the disputes between, respectively:

1) Ernst Haeckel and Rudolf Virchow;

2) Franz Boas and Madison Grant; and

3) Ashley Montagu and Carleton Coon.

The first of these rivalries, occurring as it did in Germany in the nineteenth century, is perhaps of least interest to contemporary North American audiences, being the most remote in both time and place.

However, the outcomes of the latter two disputes, occurring as they did in twentieth century America, are of much greater importance, and their outcome gave rise to, and arguably continues to shape, the current political and scientific consensus on racial matters in America, and indeed the western world, to this day.

Interestingly, these two disputes were not only about race, they were also arguably themselves racial, or at least ethnic, in character.

Thus, perhaps not uncoincidentally, whereas both Grant and Coon were Old Stock American patrician WASPs, the latter proud to trace his ancestry back among the earliest British settlers of the Thirteen Colonies, both Boas and Montagu were recent Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.[24]

Therefore, in addition to being personal, political and scientific, these two conflicts were also arguably racial, and ultimately indirectly concerned with the very definition of what it meant to be an ‘American’.

The victory of the Boasians was therefore both coincident with, and arguably both heralded and reflected (and perhaps even contributed towards, or, at least, was retrospectively adopted as a justification for), the displacement of Anglo-Americans as the culturally, socially, economically and politically dominant ethnic group in the USA, the increasing opening up of the USA to immigrants of other races and ethnicities, and the emergence of a new elite, no longer composed exclusively, or even predominantly, of people of any single specific ethnic background, but increasingly overwhelmingly disproportionately Jewish.

Sarich and Miele, to their credit, do not entirely avoid addressing the ethnic dimension to these disputes. Thus, they suggest that Boas and Montagu’s perception of themselves as ethnic outsiders in Anglo-America may have shaped their theories (p89-90).[25]

However, this is topic is explored more extensively by Kevin Macdonald in the second chapter of his controversial, anti-Semitic and theoretically flawed, The Culture of Critique (which I have reviewed here).

Boas, and his student Montagu, were ultimately to emerge victorious, not so much on account of the strength of their arguments, as on the success of their academic politicking, in particular Boas’s success in training students, including Montagu himself, who would go on to take over the social science departments of universities across America.

Among these students were many figures who were to become even more famous, and arguably more directly influential, than Boas himself, including, not only Montagu, but also Ruth Benedict and, most famous of all, the anthropologically inept Margaret Mead.[26]

Nevertheless, Sarich and Miele trace the current consensus, and sacrosanct dogma, of ‘race-denial’ ultimately to Boas, whom they credit with effectively inventing anew the modern discipline of anthropology as it exists in America:

“It is no exaggeration to say that Franz Boas (1858-1942) remade American anthropology in his own image. Through the influence of his students, Margaret Mead (Coming of Age in Samoa and Sex and Temperament in Three [Primitive] Societies[sic]), Ruth Benedict (Patterns of Culture) and Ashley Montagu (innumerable titles, especially the countless editions of Man’s Most Dangerous Myth) Boas would have more influence on American intellectual thought than Darwin did. For generations hardly anyone graduated an American college without having read at least one of these books” (p86).

Thus, today, Boas is regarded as ‘the father of American anthropology’, whereas both Grant and Coon are mostly dismissed (in Coon’s case, unfairly) as pseudo-scientists and racists.

The Legacy of Boas

As to whether the impact of Boas and his disciples was, on balance, a net positive or a net negative, Sarich and Miele are ambivalent:

“The cultural determinism of the Boasians served as a useful corrective to the genetic determinism of racial anthropology, emphasizing the variation within races, the overlap between them and the plasticity of human behavior. The price, however, was the divorcing of the science of man from the science of life in general. The evolutionary perspective was abandoned, and anthropology began its slide into the abyss of deconstructionism” (p91).

My own view is more controversial: I have come to believe that the influence of Boas on American anthropology has been almost entirely negative.

Admittedly, the ‘Nodicism’ of his rival, Grant, was indeed a complete non-starter. After all, civilization actually came quite late to Northern Europe, originating in North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, arriving in Northern Europe much later, by way the Mediterranean region.

However, this view is arguably no less preposterous than the racial egalitarianism that currently prevails as a sacrosanct contemporary dogma, and which holds that all races are exactly equal in all abilities, which, quite apart from being contradicted by the evidence, represents a manifestly improbable outcome of human evolution.

Moreover, Nordicism may have been bad science, but it was at least science – or at least purported to be science – and hence was susceptible to falsification, and was indeed soon to be decisively falsified by pre-war and post-war rise of Japan among other events and indeed scientific findings.

In contrast, as persuasively argued by Kevin Macdonald in The Culture of Critique (which I have reviewed here), Boasian anthropology was not so much a science as an anti-science (not theory but an “anti-theory” according to Macdonald: Culture of Critique: p24), because, in its radical cultural determinism and cultural relativism, it rejected any attempt to develop a general theory of societal evolution, or societal differences, as premature, if not inherently misguided.

Instead, the Boasians endlessly emphasized, and celebrated (and indeed sometimes exaggerated and fabricated), “the vast diversity and chaotic minutiae of human behavior”, arguing that such diversity precluded any general theory of social evolution as had formerly been favoured, let alone any purported ranking of societies and cultures (let alone races) as superior or inferior in relation to one another.

“The Boasians argued that general theories of cultural evolution must await a detailed cataloguing of cultural diversity, but in fact no general theories emerged from this body of research in the ensuing half century of its dominance of the profession… Because of its rejection of fundamental scientific activities such as generalization and classification, Boasian anthropology may thus be characterized more as an anti-theory than a theory of human culture” (Culture of Critique: p24).

The result was that behavioural variation between groups, to the extent there was any attempt to explain it at all, was attributed to ‘culture’. Yet, as evolutionary psychologist David Buss, writes:

“[P]atterns of local within-group similarity and between-group differences are best regarded as phenomena that require explanation. Transforming these differences into an autonomous causal entity called ‘culture’ confuses the phenomena that require explanation with a proper explanation of those phenomena. Attributing such phenomena to culture provides no more explanatory power than attributing them to God, consciousness, learning, socialization, or even evolution, unless the causal processes that are subsumed by these labels are properly described. Labels for phenomena are not proper causal explanations for them” (Evolutionary Psychology: p411).

To attribute all cultural differences simply to ‘culture’ and conclude that that is an adequate explanation is to imply that all cultural variation is simply random in nature. This amounts to effectively accepting the null hypothesis as true and ruling out a priori any attempt to generate a causal framework for explaining, or making predictions regarding, cultural differences. It therefore amounts, not to science, but to an outright rejection of science, or at least of applying science to human cultural differences, in favour of obscurantism.

Meanwhile, under the influence of postmodernism (i.e. “the abyss of deconstructionism” to which Sarich and Miele refer) much of cultural anthropology has ceased even pretending to be a science, dismissing all knowledge, science included, as mere disguised ‘ideology’, no more or less valid than the religious cosmologies, eschatologies and creation myths of the scientific and technologically primitive peoples whom anthropologists have traditionally studied, and hence precluding the falsification of post-modernist claims, or indeed any other claims, a priori.

Moreover, contrary to popular opinion, the Nordicism of figures such as Grant seems to have been rather less dogmatically held to, both in the scientific community and society at large, than is the contemporary dogma of racial egalitarianism.

Indeed, quite apart from the fact that it was not without eminent critics even in its ostensible late-nineteenth, early-twentieth century heyday (not least Boas himself), the best evidence for this is the speed with which this belief system was abandoned, and subsequently demonized, in the coming decades.

In contrast, even with the findings of population genetics increasing apace, the dogmas of both race denial and racial egalitarianism, while increasingly scientifically indefensible, seemingly remain ever more entrenched in the universities.

Digressions: ‘Molecular Clocks’, Language and Human Evolution

Sarich and Miele’s next chapter, ‘Resolving the Primate Tree’, recounts how the ‘molecular clock’ method of determining when species (and races) diverged was discovered.

To summarize: Geneticists discovered they could estimate the time when two species separated from one another by measuring the extent to which the two species differ in selectively-neutral genetic variation – in other words, those parts of the genome that do not affect an organism’s phenotype in such a way as to affect its fitness, are therefore not subject to selection pressures and hence mutate at a uniform rate, hence serving as a ‘clock’ by which to measure when the species separated from one another.

The following chapter, ‘Homo Sapiens and Its Races’, charts the application of the ‘molecular clock’ method to human evolution, and in particular to the evolution of human races.

The molecular clock method of dating the divergence of species from one another is certainly relevant to the race question, since it allows us to estimate, not only when our ancestors split from those of the chimpanzee, but also when different human races separated from one another – though this latter question is somewhat more difficult to determine using this method, since it is complicated by the fact that races can continue to interbreed with one another even after their initial split, whereas species, once they have become separate species, by definition no longer interbreed, though there may be some interbreeding during the process of speciation itself (i.e. when the separate lineages were still only races or populations of the same species).

However, devoting a whole chapter to a narrative describing how the molecular clock methodology was developed seems excessive in a book ostensibly about human race differences, and is surely an unnecessary digression.

Thus, one suspects the attention devoted to this topic by the authors reflects the central role played by one of the book’s co-authors (Vincent Sarich) in the development of this scientific method. This chapter therefore permits Sarich to showcase his scientific credentials and hence lends authority to his later more controversial pronouncements in subsequent chapters.

The following chapter, ‘The Two Miracles that Made Mankind’, is also somewhat off-topic. Here, Sarich and Miele address the question of why it was that our own African ancestors who ultimately outcompeted and ultimately displaced rival species of hominid.[27]

In answer, they propose, plausibly but not especially originally, that our descendants outcompeted rival hominids on account of one key evolutionary development in particular – namely, our evolution of a capacity for spoken language.

Defining ‘Race’

At last, in Chapters Seven and Eight, after a hundred and sixty pages and over half of the entire book, the authors address the topic which the book’s title suggested would be its primary focus – namely, the biology of race differences.

The first of these is titled ‘Race and Physical Differences’, while the next is titled ‘Race and Behavior’.

Actually, however, both chapters begin by defending the race concept itself.

Whether the human race is divisible into races ultimately depends on how one defines ‘races’. Arguments are to whether human races exist therefore often degenerate into purely semantic disputes regarding the meaning of the word ‘race’.

For their purposes, Sarich and Miele themselves define ‘races’ as:

“Populations, or groups of populations, within a species, that are separated geographically from other such populations or groups of populations and distinguishable from them on the basis of heritable features” (p207).[28]

There is, of course, an obvious problem with this definition, at least when applied to contemporary human populations – namely, members of different human races are often no longer “separated geographically” from one another, largely due to recent migrations and population movements.

Thus, today, people of many different racial groups can be found in a single city, like, say, London.

However, the key factor is surely, not whether racial groups remain “separated geographically” today, but rather whether they were “separated geographically” during the period during which they evolved into separate races.

To answer this objection, Sarich and Miele’s definition of ‘races’ should be altered accordingly.

Races as ‘Fuzzy Sets’

Sarich and Miele protest that other authors have, in effect, defined races out of existence by semantic sophistry, namely by defining the word ‘race’ in such a way as to rule out the possibility of races a priori.

Thus, some proposed definitions demand that, in order to qualify as true ‘races’, populations must have discrete, non-overlapping boundaries, with no racially-mixed, clinal or hybrid populations to blur the boundaries.

However, Sarich and Miele point out, any populations satisfying this criterium would not be ‘races’ at all, but rather entirely separate species, since, as I have discussed previously, it is the question of interfertility and reproductive isolation that defines a ‘species’ (p209).[29]

In short, as biologist John Baker, in his excellent Race (reviewed here), also pointed out, since ‘race’ is, by very definition, a sub-specific classification, it is inevitable that members of different races will sometimes interbreed with one another and produce mixed, hybrid or clinal populations at their borders, because, if they did not interbreed with one another, then they would not be members of different races but rather of entirely separate species.

Thus, the boundaries between subspecies are invariably blurred or clinal in nature, the phenomenon being so universal that there is even a biological term for it, namely ‘intergradation’.

Of course, this means that the dividing line where one race is deemed to begin and another to end will inevitably be blurred. However, Sarich and Miele reject the notion that this means races are purely artificial or a social construction.

“The simple answer to the objection that races are not discrete, blending into one another as they do is this: They’re supposed to blend into one another and categories need not be discrete. It is not for us to impose our cognitive difficulties upon the Nature.” (p211)

Thus, they characterize races as “fuzzy sets” – which they describe as a recently developed mathematical concept that has nevertheless been “revolutionarily productive” (p209).

By analogy, they discuss our colour perception when observing rainbows, observing:

“Red… shade[s] imperceptibly into orange and orange into yellow but we have no difficulties in agreeing as to where red becomes orange, and orange yellow” (p208-9).

However, this is perhaps an unfortunate analogy. After all, physicists and psychologists are in agreement that different colours, as such, don’t really exist – at least not outside of the human minds that perceive and recognise them.[30]

Instead, the electromagnetic spectrum varies continuously. Colours are imposed on only by human visual system as a way of interpreting this continuous variation.[31]

If racial differences were similarly continuous, then surely it would be inappropriate to divide peoples into racial groups, because wherever one drew the boundary would be entirely arbitrary.[32]

Yet a key point about human races is that, as Sarich and Miele put it:

“[Although] races necessarily grade into one another, but they clearly do not do so evenly” (p209).

In other words, although racial differences are indeed clinal and continuous in nature, the differentiation does not occur at a constant and uniform rate. Instead, there is some clustering and definite if fuzzy boundaries are nevertheless discernible.

As an illustration of such a fuzzy but discernible boundary, Sarich and Miele give the example of the Sahara Desert, which formerly represented, and to some extent still does represent, a relatively impassable obstacle (a “a geographic filter”, in Sarich and Miele’s words: p210) that impeded population movement and hence gene flow for millennia.

“The human population densities north and south of the Sahara have long been, and still are, orders of magnitude greater than in the Sahara proper, causing the northern and southern units to have evolved in substantial genetic independence from one another” (p210).

The Sahara hence represented the “ancient boundary” between the racial groups once referred to by anthropologists as the ‘Caucasoid’ and ‘Negroid’ races, politically incorrect terms which, according to Sarich and Miele, although unfashionable, nevertheless remain useful (p209-10).

Analogously, anthropologist Stanley Garn reports:

“The high and uninviting mountains that mark the Tibetan-Indian border… have long restricted population exchange to a slow trickle” (Human Races: p15).

Thus, these mountains (the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau), have traditionally marked the boundary between the ‘Caucasoid’ and what was once termed the ‘Mongoloid’ race.[33]

Meanwhile, other geographic barriers were probably even more impassable. For example, oceans almost completely prevented gene-flow between the Americas and the Old World, save across the Berring strait between sparsely populated Siberia and Alaska, for millennia, such that Amerindians remained almost completely reproductively isolated from Eurasians and Africans.

Similarly, genetic studies suggest that Australian Aboriginals were genetically isolated from other populations, including neighbouring South-East Asians and Polynesians, for literally thousands of years.

Thus, anthropologist Stanley Garn concludes:

“The facts of geography, the mountain ranges, the deserts and the oceans, have made geographical races by fencing them in” (Human Races: p15).

However, with improved technologies of transportation – planes, ocean-going vessels, other vehicles – such geographic boundaries are becoming increasingly irrelevant.

Thus, increased geographic mobility, migration, miscegenation and intermarriage mean that the ‘fuzzy’ boundaries of these ‘fuzzy sets’ are fast becoming even ‘fuzzier’.

Thus, if meaningful boundaries could once be drawn between races, and even if they still can, this may not be the case for very much longer.

However, it is important to emphasize that, even if races didn’t exist, race differences still would. They would just vary on a continuum (or a ‘cline’, to use the preferred biological term).

To argue that races differences do not exist simply because they are continuous and clinal in nature would, of course, be to commit a version of the ‘continuum fallacy’ or ‘sorties paradox’, also sometimes called the ‘fallacy of the heap’ or ‘fallacy of the beard’.

Moreover, just as populations differ in, for example, skin colour on a clinal basis, so they could also differ in psychological traits (such as average intelligence and personality) in just the same way.

Thus, paradoxically, the non-existence of human races, even if conceded for the sake of argument, is hardly a definitive, knock-down argument against the existence of innate race differences in intelligence, or indeed other racial differences, even though it is usually presented as such by those who espouse this view.

Whether ‘races’ exist is debatable and depends on precisely how one defines ‘races’—whether race differences exist, however, is surely beyond dispute.

Debunking Diamond

The brilliant and rightly celebrated scientific polymath and popular science writer Jared Diamond, in an influential article published in Discovery magazine, formulated another even less persuasive objection to the race concept as applied to humans (Diamond 1994).

Here, Diamond insisted that racial classifications among humans are entirely arbitrary, because different populations can be grouped into different ways if one uses different characteristics by which to group them.

Thus, if we classified races, not by skin colour, but rather by the prevalence of the sickle cell gene or of lactase persistence, then we would, he argues, arrive at very different classifications. For example, he explains:

“Depending on whether we classified ourselves by antimalarial genes, lactase, fingerprints or skin color, we could place Swedes in the same race as (respectively) either Xhosas, Fulani, the Ainu of Japan or Italians” (p164).

Each of these classifications, Diamond insists, would be “equally reasonable and arbitrary” (p164).

To these claims, Sarich and Miele respond:

“Most of us, upon reading these passages, would immediately sense that something was very wrong with it, even though one might have difficulty specifying just what” (p164).

Unfortunately, however, Sarich and Miele are, in my view, not themselves very clear in explaining precisely what is wrong with Diamond’s argument.

Thus, one of Sarich and Miele’s grounds for rejecting this argument is that:

“The proportion of individuals carrying the sickle-cell allele can never go above about 40 percent in any population, nor does the proportion of lactose-competent adults in any population ever approach 100 percent. Thus, on the basis of the sickle-cell gene, there are two groups… of Fulani, one without the allele, the other with it. So those Fulani with the allele would group not with other Fulani, but with Italians with the allele” (p165).

Here their point seems to be that it is not very helpful to classify races by reference to a trait that is not shared by all members of any race, but rather differs only in relative prevalence.

Thus, they conclude:

“The concordance issue… applies within groups as well as between them. Diamond is dismissive of the reality of the Fulani–Xhosas African racial unit because there are characters discordant with it [e.g. lactase persistence]… Well then, one asks in response, what about the Fulani unit itself? After all, exactly the same argument could be made to cast the reality of the category ‘Fulani’ into doubt” (p165).

However, this conclusion seems to represent exactly what many race deniers do indeed argue – namely that all racial and ethnic groups are indeed pure social constructs with no basis in biology, including terms such as ‘Fulani’ and ‘Italian’, which are, they would argue, as biologically meaningless and socially constructed as terms such as ‘Negroid’ and ‘Caucasoid’.[34]

After all, if a legitimate system of racial classification indeed demands that some Fulani tribesmen be grouped in the same race as Italians while others are grouped in an entirely different racial taxa, then this does indeed seem to suggest racial classifications are arbitrary and unhelpful.

Moreover, the fact that there is much within-population variation in genes such as those coding for sickle-cell or lactase persistence surely only confirms Richard Lewontin’s famous argument (see below) that there is far more genetic variation within groups than between them.

Sarich and Miele’s other rejoinder to Diamond is, in my view, more apposite. Unfortunately, however, they do not, in my opinion, explain themselves very well.

They argue that:

“[The absence of the sickle-cell gene] is a meaningless association because the character involved (the lack of the sickle-cell allele) is an ancestral human condition. Associating Swedes and Xhosas thus says only that they are both human, not a particularly profound statement” (p165).

What I think Sarich and Miele are getting at here is that, whereas Diamond proposes to classify groups on the basis of a single characteristic, in this case the sickle-cell gene, most biologists favour a so-called cladistic taxonomy, where organisms are grouped together not on the basis of shared characteristics as such at all, but rather on the basis of shared ancestry.

In other words, orgasms are grouped together because they are more closely related to one another (or shared a common ancestor more recently) than are other organisms that are put into a different group.

From this perspective, shared characteristics are relevant only to the extent they are (interpreted as) homologous and hence as evidence of shared ancestry. Traits that evolved independently through convergent or parallel evolution (i.e. in response to analogous selection pressures in separate lineages) are irrelevant.

Yet the genes responsible for lactase persistence, one of the traits used by Diamond to classify populations, evolved independently in different populations through gene-culture co-evolution in concert with the independent development of dairy farming in different parts of the world, an example of convergent evolution that does not suggest relatedness. Indeed, not only did lactase continuance evolve independently in different races, it also seems to have evolved quite different mutations in different genes (Tishkoff et al 2007).[35]

However, Diamond’s proposed classification is especially preposterous. Even pre-Darwinian systems of taxonomy, which did indeed classify species (and subspecies) on the basis of shared characteristics rather than shared ancestry, nevertheless did so on the basis of a whole suite of traits that were clustered together.

In contrast, Diamond proposes to classify races on the basis of a single trait, apparently chosen arbitrarily – or, more likely, to illustrate the point he is attempting to make.

Genetic Differences

In an even more influential and widely-cited paper, Marxist biologist Richard Lewontin claimed that 85% of genetic variation occurred within populations and only 6% accounted for the differences between races (Lewontin 1972).[36]

The most familiar rejoinder to Lewontin’s argument is that of Edwards who pointed out that, while Lewontin’s figures are correct when one looks at individual genetic loci, if one looks at multiple loci, then one can identify an individual’s race with precision that approaches 100% the more loci that are used (Edwards 2003).

However, Edwards’ paper was only published in 2003, just a year before ‘Race: The Reality of Human Differences’ itself came off the presses, so Sarich and Miele may not have been aware of Edwards’ critique at the time they actually wrote the book.[37]

Perhaps for this reason, then, Sarich and Miele respond rather differently to Lewontin’s arguments.

First, they point out:

“[Lewontin’s] analysis omits a third level of variability–the within-individual one. The point is that we are diploid, getting one set of chromosomes from one parent and a second from the other” (p168-9).

Thus Sarich and Miele conclude:

“The… 85 percent will then split half and half (42.5%) between the intra- and inter-individual within-population comparisons. The increase in variability in between-population comparisons is thus 15 percent against the 42.5 percent that is between individual within-population. Thus, 15/4.5 = 32.5 percent, a much more impressive and, more important, more legitimate value than 15 percent.” (p169).

However, this seems to me to be just playing around with numbers in order to confuse and obfuscate.

After all, if as Lewontin claims, most variation is within-group rather than between group, then, even if individuals mate endogamously (i.e. with members of the same group as themselves), offspring will show substantial variation between the portion of genes they inherit from each parent.

But, even if some of the variation is therefore within-individual, this doesn’t change the fact that it is also within-group.

Thus, the claim of Lewontin that 85% of genetic variation is within-group remains valid.

Morphological Differences

Sarich and Miele then make what seems to me to be a more valid and important objection to Lewontin’s figures, or at least to the implication he and others have drawn from them, namely that racial differences are insignificant. Again, however, they do not express themselves very clearly.

Their argument seems to be that, if we are concerned with the extent of physiological and psychological differentiation between races, then it actually makes more sense to look directly at morphological differences, rather than genetic differences.

After all, a large proportion of our DNA may be of the nonfunctional non-coding or ‘junk’ variety, some of which may have little or no effect an organism’s phenotype.

Thus, in their chapter ‘Resolving the Primate Tree’, Sarich and Miele themselves claim that:

“Most variation and change at the level of DNA and proteins have no functional consequences” (p121; p126).

They conclude:

“Not only is the amount of between-population genetic variation very small by the standards of what we observe in other species… but also… most variation that does exist has no functional, adaptive significance” (p126).

Thus, humans and chimpanzees may share around 98% of each other’s DNA, but this does not necessarily mean that we are 98% identical to chimpanzees in either our morphology, or our psychology and behaviour. The important thing is what the genes in question do, and small numbers of genes can have great effects while others (e.g. non-coding DNA) may do little or nothing.[38]

Indeed, one theory has it that such otherwise nonfunctional biochemical variation may be retained within a population by negative frequency dependent selection because different variants, especially when recombined in each new generation by sexual reproduction, confer some degree of protection against infectious pathogens.

This is sometimes referred to as ‘rare allele advantage’, in the context of the ‘Red Queen theory’ of host-parasite co-evolutionary arms race.

Thus, evolutionary psychologists John Tooby and Leda Cosmides explain:

“The more alternative alleles exist at more loci—i.e., the more genetic polymorphism there is—the more sexual recombination produces genetically differentiated offspring, thereby complexifying the series of habitats faced by pathogens Most pathogens will be adapted to proteins and protein combinations that are common in a population, making individuals with rare alleles less susceptible to parasitism, thereby promoting their fitness. If parasitism is a major selection pressure, then such frequency-dependent selection will be extremely widespread across loci, with incremental advantages accruing to each additional polymorphic locus that varies the host phenotype for a pathogen. This process will build up in populations immense reservoirs of genetic diversity coding for biochemical diversity” (Tooby & Cosmides 1990: p33).

Yet, other than conferring some resistance to fast-evolving pathogens, such “immense reservoirs of genetic diversity coding for biochemical diversity” may have little adaptive or functional significance and have little or no effect on other aspects of an organism’s phenotype.

Lewontin’s figures, though true, are therefore potentially misleading. To see why, behavioural geneticist Glayde Whitney suggested that we “might consider the extent to which humans and macaque monkeys share genes and alleles”. On this basis, he reported:

“If the total genetic diversity of humans plus macaques is given an index of 100 percent, more than half of that diversity will be found in a troop of macaques or in the [then quite racially homogenous] population of Belfast. This does not mean Irishmen differ more from their neighbors than they do from macaques — which is what the Lewontin approach slyly implies” (Whitney 1997).

Anthropologist Peter Frost, in an article for Aporia Magazine critiquing Lewontin’s analysis, or at least the conclusions he and others have drawn from them, cites several other examples where:

“Wild animals… show the same pattern of genes varying much more within than between populations, even when the populations are related species and, sometimes, related genera (a taxonomic category that ranks above species and below family)“ (Frost 2023).

However, despite the minimal genetic differentiation between races, different human races do differ from one another morphologically to a significant degree. This much is evident simply from looking at the facial morphology, or bodily statures, of people of different races – and indirectly apparent by observing which races predominate in different athletic events at the Olympics.

Thus, Sarich and Miele point out, when one looks at morphological differences, it is clear that, at least for some traits, such as “skin color… hair form… stature… body build”, within-group variation does not always dwarf between-group variation (p167).

On the contrary, Sarich and Miele observe:

“Group differences can be much greater than the individual differences within them; in, for example, hair from Kenya and Japan, or body shape for the Nuer and Inuit” (p218).

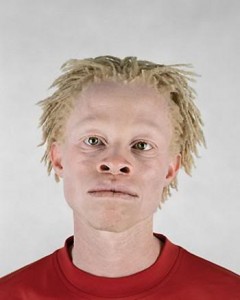

Indeed, in respect of some traits, there may be almost no overlap between groups. For example, excepting suffers of rare, abnormal and pathological conditions like albinism, even the lightest complexioned Nigerian is still darker in complexion and skin colour than is the darkest indigenous Swede.

If humans differ enough genetically to cause the obvious (and not so obvious) morphological differences between races, differences which are equally obviously genetic in origin, then it necessarily follows that they also differ enough genetically to allow for a similar degree of biological variation in psychological traits, such as personality and intelligence.

That human populations are genetically quite similar to one another indicates, Sarich and Miele concede, that the different races separated and became reproductively isolated from one another only quite recently, such that random variation in selectively-neutral DNA has not had sufficient time to accumulate through random mutation and genetic drift.

However, the fact that, within this short period, quite large morphological differences have nevertheless evolved suggests the presence of strong selective pressures selecting for such morphological differentiation.

They cite archaeologist Glynn Isaac as arguing:

“It is the Garden-of-Eden model [i.e. ‘out of Africa theory’], not the regional continuity model [i.e. multiregionalism], that makes racial differences more significant functionally… because the amount of time involved in the raciation process is much smaller, but the degree of racial differentiation is the same and, for human morphology, large. The shorter the period of time required to produce a given amount of morphological difference, the more selectively/adaptively/functionally important those differences become” (p212).

Thus, Sarich and Miele conclude:

“So much variation developing in so short a period of time implies, indeed almost requires, functionality; there is no good reason to think that behavior should somehow be exempt from this pattern of functional variability” (p173).

In other words, if different races have been subjected to divergent selection pressures that have led them to diverge morphologically, then these same selection pressures will almost certainly also have led them to psychologically diverge from one another.

Indeed, at least one well-established morphological difference seems to directly imply a corresponding psychological difference – namely, differences in brain size as between races would seem to suggest differences in intelligence, as I have discussed in greater detail both previously and below.

Measuring Morphological Differences

Continuing this theme, Sarich and Miele argue that human racial groups actually differ more from one another morphologically than do many non-human mammals that are regarded as entirely separate species.

Thus, Sarich quotes himself as claiming:

“Racial morphological distances within our species are, on the average, about equal to the distances among species within other genera of mammals. I am not aware of another mammalian species whose constituent races are as strongly marked as they are in ours… except, of course, for dogs” (p170).

I was initially somewhat skeptical of this claim. Certainly, it seems to us that, say, a black African looks very different from an East Asian or a white European. However, this may simply be because, being human, and in close day-to-day contact with humans, we are far more readily attuned to differences between humans than differences between, say, chimpanzees, or wolves, or sheep.[39]

Indeed, there is even evidence that we possess an innate domain-specific ‘face recognition module’ that evolved to help us to distinguish between different individuals, and which seems to be localized in certain areas of the brain, including the so-called ‘fusiform facial area’, which is located in the fusiform gyrus.

Indeed, as I have already noted in an earlier endnote, a commenter on an earlier version of this book review plausibly suggested that our tendency to group individuals by race could represent a by-product of our facial recognition faculty.

However, the claim that the morphological differences between human races are comparable in magnitude to those between some different species or nonhuman organism is by no means original to Sarich and Miele.

For example, John R Baker makes a similar claim in his excellent book, Race (which I have reviewed here), where he asserts:

“Even typical Nordids and typical Alpinids, both regarded as subraces of a single race (subspecies), the Europid [i.e. Caucasoid), are very much more different from one another in morphological characters—for instance in the shape of the skull—than many species of animals that never interbreed with one another in nature, though their territories overlap” (Race: p97).

Thus, Baker claims:

“Even a trained anatomist would take some time to sort out correctly a mixed collection of the skulls of Asiatic jackals (Canis aureus) and European red foxes (vulpes vulpes), unless he had made a special study of the osteology of the Canidae; whereas even a little child, without any instruction whatever, could instantly separate the skulls of Eskimids from those of Lappids” (Race: p427).

Indeed, Darwin himself made a not dissimilar claim in The Descent of Man, where he observed:

“If a naturalist, who had never before seen a Negro, Hottentot, Australian, or Mongolian, were to compare them, he would at once perceive that they differed in a multitude of characters, some of slight and some of considerable importance. On enquiry he would find that they were adapted to live under widely different climates, and that they differed somewhat in bodily constitution and mental disposition. If he were then told that hundreds of similar specimens could be brought from the same countries, he would assuredly declare that they were as good species as many to which he had been in the habit of affixing specific names” (The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex).

However, Sarich and Miele attempt to go one better than both Baker and Darwin – namely, by not merely claiming that human races differ morphologically from one another to a similar or greater extent than many separate species of non-human animal, but also purporting to prove this claim statistically as well.

Thus, relying on “cranial/facial measurements on 29 human populations, 2,500 individuals 28 measurements… 17 measurements on 347 chimpanzees… and 25 measures on 590 gorillas” (p170), Sarich and Miele’s conclusion is dramatic: reporting the “percent increases in distance going from within-group to between-group comparisons of individuals”, measured in terms of “the percent difference per size corrected measurement (expressed as standard deviation units)”, a greater percentage of the total variation among humans is found between different human groups than is found between some separate species of non-human primate.

Thus, Sarich and Miele somewhat remarkably conclude:

“Racial morphological distances in our species [are] much greater than any seen among chimpanzees or gorillas, or, on the average, some tenfold greater than those between the sexes” (p172-3).

Interestingly, and consistent with the general rule that Steve Sailer has termed ‘Rushton’s Rule of Three’, whereby blacks and Asians respectively cluster at opposite ends of a racial spectrum for various traits, Sarich and Miele report:

“The largest differences in Howells’s sample are found when comparing [black sub-Saharan] Africans with either Asians or Asian-derived (Amerindian) populations” (p172).

Thus, for example, measured in this way, the proportion of the total variation that separates East Asians from African blacks is more than twice that separating chimpanzees from bonobos.

This, however, is perhaps a misleading comparison, since chimpanzees and bonobos are known to be morphologically very similar to one another, to such an extent that, although now recognized as separate species, they were, until quite recently, considered as merely different subspecies of a single species.

Another problem with Sarich and Miele’s conclusion is that, as they themselves report, it relies entirely on “cranial/facial measurements” and thus it is unclear whether the extent of these differences generalize to other parts of the body.

Yet, despite this limitation, Sarich and Miele report their results as applying to “racial morphological distances” in general, not just facial and cranial differences.

Finally, Sarich and Miele’s analysis in this part of their book is rather technical.

I feel that the more appropriate place to publish such an important and provocative finding would have been a specialist journal in biological anthropology, which would, of course, include a full methodolgy section and also be subject to full peer review before publication.

Domestic Dog Breeds and Human Races

Sarich and Miele argue that the only mammalian species with greater levels of morphological variation between subspecies than humans are domestic dogs.

Thus, psychologist Daniel Freedman, writing in 1979, claimed:

“A breed of dog is a construct zoologically and genetically equivalent to a race of man” (Human Sociobiology: p144).

Of course, morphologically, dog breeds differ enormously, far more than human races.

However, the logistical problems of a Chihuahua mounting a mastiff notwithstanding, all are thought to be capable of interbreeding with one another, and also with wild wolves, and are hence all dog breeds, together with wild wolves, are generally considered by biologists to represent a single species.

Moreover, Sarich and Miele report that genetic differences between dog breeds, and between dogs and wolves, were so slight that, at the time Sarich and Miele were writing, researchers had only just begun to be able to genetically distinguish some dog breeds from others (p185).

Of course, this was written in 2003, and genetic data in the years since then has accumulated at a rapid pace.

Moreover, even then, one suspects that the supposed inability of geneticists to distinguish one dog breed from another reflected, not so much the limited genetic differentiation between breeds, as the fact that, understandably, far fewer resources had been devoted to decoding the canine genome that were devoted to decoding that of humans ourselves.

Thus, today, far more data is available on the genetic differences between breeds and these differences have proven, unsurprisingly given the much greater morphological differences between dog breeds as compared to human races, to be much greater than those between human populations.

For example, as I have discussed above, Marxist-biologist Richard Lewontin famously showed that, for humans, there is far greater genetic variation within races than between races (Lewontin 1972).

It is sometimes claimed that the same is true for dog breeds. For example, self-styled ‘race realist’ and ‘white advocate’, and contemporary America’s leading white nationalist public intellectual (or at least the closest thing contemporary America has to a white nationalist public intellectual), Jared Taylor claims, in a review of Edward Dutton’s Making Sense of Race, that:

“People who deny race point out that there is more genetic variation within members of the same race than between races — but that’s true for dog breeds, and not many people think the difference between a terrier and a pug is all in our minds” (Taylor 2021).

Actually, however, Taylor appears to be mistaken.

Admittedly, some early mitochondrial DNA studies did seemingly support this conclusion. Thus, Coppinger and Schneider reported in 1994 that:

“Greater mtDNA differences appeared within the single breeds of Doberman pinscher or poodle than between dogs and wolves… To keep the results in perspective, it should be pointed out that there is less mtDNA difference between dogs, wolves and coyotes than there is between the various ethnic groups of human beings, which are recognized as belonging to a single species” (Coppinger & Schneider 1994).

However, while this may be true for mitochondrial DNA, it does not appear to generalize to the canine genome as a whole. Thus, in her article ‘Genetics and the Shape of Dogs’ geneticist Elaine Ostrander, an expert on the genetics of domestic dogs, reports:

“Genetic variation between dog breeds is much greater than the variation within breeds. Between-breed variation is estimated at 27.5 percent. By comparison, genetic variation between human populations is only 5.4 percent” (Ostrander 2007).[40]

However, the fact that both morphological and genetic differentiation between dog breeds far exceeds that between human races does not necessarily mean that an analogy between dog breeds and human races is entirely misplaced.

All analogies are imperfect, otherwise they would not be analogies, but rather identities (i.e. exactly the same thing).

Indeed, one might argue that dog breeds provide a useful analogy for human races precisely because the differences between dog breeds are so much greater, since this allows us to see the same principles operating but on a much more magnified scale and hence brings them into sharper focus.

Breed and Behaviour

As well as differing morphologically, dog breeds are also thought to differ behaviourally as well.

Anecdotally, some breeds are said to be affectionate and ‘good with children’, others standoffish, independent, territorial and prone to aggression, either with strangers or with other dogs.

For example, psychologist Daniel Freedman, whose study of average differences in behaviour among both dog breeds, conducted as part of his PhD, and his later analogous studies of differences in behaviour of neonates of different races, are discussed by Sarich and Miele in their book (p203-7), observed:

“I had worked with different breeds of dogs and I had been struck by how predictable was the behavior of each breed” (Human Sociobiology: p144).

Freedman’s scientifically rigorous studies of breed differences in behaviour confirmed that at least some such differences are indeed real and seem to have an innate basis.

Thus, studying the behaviours of newborn puppies to minimize the possibility of environmental effects affecting behaviour differences, just as he later studied differences in the behaviour of human neonates, Freedman reports:

“The breeds already differed in behavior. Little beagles were irrepressibly friendly from the moment they could detect me, whereas Shetland sheepdogs were most sensitive to a loud voice or the slightest punishment; wire-haired terriers were so tough and aggressive, even as clumsy three-week olds, that I had to wear gloves in playing with them; and, finally, basenjis, barkless dogs originating in central Africa, were aloof and independent” (Human Sociobiology: p145).

Similarly, Hans Eysenck reports the results of a study of differences in behaviour between different dog breeds raised under different conditions then left alone in a room with food they had been instructed not to eat. He reports:

“Basenjis, who are natural psychopaths, ate as soon as the trainer had left, regardless of whether they had been brought up in the disciplined or the indulgent manner. Both groups of Shetland sheep dogs, loyal and true to death, refused the food, over the whole period of testing, i.e. eight days! Beagles and fox terriers responded differentially, according to the way they had been brought up; indulged animals were more easily conditioned, and refrained longer from eating. Thus, conditioning has no effect on one group, regardless of upbringing—has a strong effect on another group, regardless of upbringing—and affects two groups differentially, depending on their upbringing” (The IQ Argument: p170).

These differences often reflect the purpose for which the dogs were bred. For example, breeds historically bred for dog fighting (e.g. Staffordshire bull berriers) tend to be aggressive with other dogs, but not necessarily with people; those bred as guard dogs (e.g. mastiffs, Dobermanns) tend to be highly territorial; those bred as companions sociable and affectionate; while others have been bred to specialize in certain highly specific behaviours at which they excel (e.g. pointers, sheep dogs).

For example, the author of one recent study of behavioural differences among dog breeds interpreted her results thus:

“Inhibitory control may be a valued trait in herding dogs, which are required to inhibit their predatory responses. The Border Collie and Australian Shepherd were among the highest-scoring breeds in the cylinder test, indicating high inhibitory control. In contrast, the Malinois and German Shepherd were some of the lowest-scoring breeds. These breeds are often used in working roles requiring high responsiveness, which is often associated with low inhibitory control and high impulsivity. Human-directed behaviour and socio-cognitive abilities may be highly valued in pet dogs and breeds required to work closely with people, such as herding dogs and retrievers. In line with this, the Kelpie, Golden Retriever, Australian Shepherd, and Border Collie spent the largest proportion of their time on human-directed behaviour during the unsolvable task. In contrast, the ability to work independently may be important for various working dogs, such as detection dogs. In our study, the two breeds which were most likely to be completely independent during the unsolvable task (spending 0% of their time on human-directed behaviour) were the German Shepherd and Malinois” (Juntilla et al 2022).

Indeed, recognition of the different behaviours of dog breeds even has statutory recognition, with controversial breed-specific legislation restricting the breeding, sale and import of certain so-called dangerous dog breeds and ordering their registration, neutering and in some cases destruction.

Of course, similar legislation restricting the import and breeding, let alone ordering the neutering or destruction, of ‘dangerous human races’ (perhaps defined by reference to differences in crime rates) is currently politically unthinkable.

Therefore, as noted above, breed-specific legislation is the rough canine equivalent of the Nuremberg Laws.

Breed Differences in Intelligence

In addition, just as there are differences between human races in average IQ (see below; see also here, here and especially here) so some studies have suggested that, on average, dog breeds differ in average intelligence.

However, there are some difficulties, for these purposes, in measuring, and defining, what constitutes intelligence among domestic dogs.[41]

Since the subject of race differences in intelligence almost always lurks in the background of any discussion of the biology of race, and, since this topic is indeed discussed at some length by Sarich and Miele in a later chapter (and indeed in a later part of this review), it is perhaps worth discussing some of these difficulties and the extent to which they mirror similar controversies regarding how to define and measure human intelligence, especially differences between races.

Thus, research by Stanley Coren, reported in his book, The Intelligence of Dogs, and also widely reported upon in the popular press, purported to rank dog breeds by their intelligence.

However, the research in question, or at least the part reported upon in the media, actually seems to have relied exclusively on measurements of the ability of the different dogs to learn, and obey, new commands from their masters/owners with the minimum of instruction.[42]

Moreover, this ability also seems, in Coren’s own account, to have been assessed on the basis of the anecdotal impression of dog contest judges, rather then direct quantitative measurement of behaviour.

Thus, the purportedly most intelligent dogs were those able to “learn a new command in less than five exposures and obey at least 95 percent of the time”, while the purportedly least intelligent were those who required “more than 100 repetitions and obey around 30 percent of the time”.

An ability to obey commands consistently with a minimum of instruction does indeed require a form and degree of social intelligence – namely the capacity to learn and understand the commands in question.

However, such a means of measurement not only measures only a single quite specific type of intelligence, it also measures another aspect of canine psychology that is not obviously related to intelligence – namely, obedience, submissiveness and rebelliousness.

This is because complying with commands requires not only the capacity to understand commands, but also the willingness to actually obey them.